This is part 1 in a series of tutorials in which we explore methods for robot localization: the problem of tracking the location of a robot over time with noisy sensors and noisy motors, which is an important task for every autonomous robot, including self-driving cars.

The methods that we will learn are generic in nature, in that they can be used for various other tasks that involve rational decision making in the face of uncertainty. We will, for the main part, deal with filtering, which is a general method for estimating variables from noisy observations over time. In particular, we will explain the Bayes Filter and some of its variants – the Histogram Filter, the Kalman Filter and the Particle Filter. We will show the benefits and shortcomings of each of these algorithms and see how they can be applied to the robot localization problem.

Motivation

The traditional approach in reasoning over time involves strict logical inference. In order for this to work, a few assumptions have to be made about the environment we wish to make decisions in. For instance, the environment has to be fully observable, which means that at any point in time we can exactly measure each aspect of the environment that is relevant to our decision making. Additionally, the environment needs to be deterministic, which means that, given the state of the environment at a certain point in time and a decision we choose, the resulting state of the environment is already determined – there is no randomness whatsoever. Last but not least, the environment has to be static, which basically means that it waits for us to make our decision before it changes.

None of these assumptions hold in realistic environments. We can never measure every aspect of an environment that might have an influence on the decision making. We can, however, use sensors to measure a small portion of the environment, but even this small portion we can not measure with complete certainty. We call such environments partially observable.

Whether realistic environments are deterministic or not is actually an unanswered philosophical question. At least for humans and agents, it appears to be non-deterministic, because even though we know physical laws that allow us to describe most natural processes, there are just too many influential factors that we are unable to model precisely (e.g. wind turbulence causing a seemingly random change in the trajectory of a flying ball). Regardless of the nondeterminism, we can usually tell what is likely to happen and what is unlikely to happen. Thus, we call realistic environments stochastic. Moreover, realistic environments are dynamic as opposed to static – they are always changing. For a more thorough treatise of the nature of environments cf. [NORVIG, pp. 40 – 46].

All of these properties of realistic environments result in uncertainty about the state of the world. It is a big challenge to make rational decisions in the face of uncertainty. Humans do a great job at this every day. Even though we can never know the true state of the world and predict what is going to happen next and how we should act to achieve a desired outcome, we still manage to achieve many of our goals remarkably well. We do this by maintaining a belief about the state of the world at a certain point in time, which we arrive at by both prediction and observation. This belief can be thought of as a probability distribution over all the possible states of the world, conditioned by our observations. Given a belief, we can, for each possible decision, determine the probabilities of each possible outcome. After that, we choose the decisions that are most probable to achieve a desired goal state, maximize a performance measure, or the like. This behavior can reasonably be called rational. Of course, we do not actually maintain precise probability distributions in our brains and carry out calculations, but this is a way of imagining how this cognitive ability of ours roughly works and it gives us a first idea of how it can be implemented algorithmically.

It is a difficult but interesting task to implement such a behavior for autonomous agents. The purpose of this text is to give an insight into how the first half can be done – the task of maintaining a belief about the state of an environment that is updated over time through making predictions according to a model of how the system develops, interpreting periodically arriving, noisy observations (more specifically, sensor measurements) and incorporating them into the belief.

Robot Localization

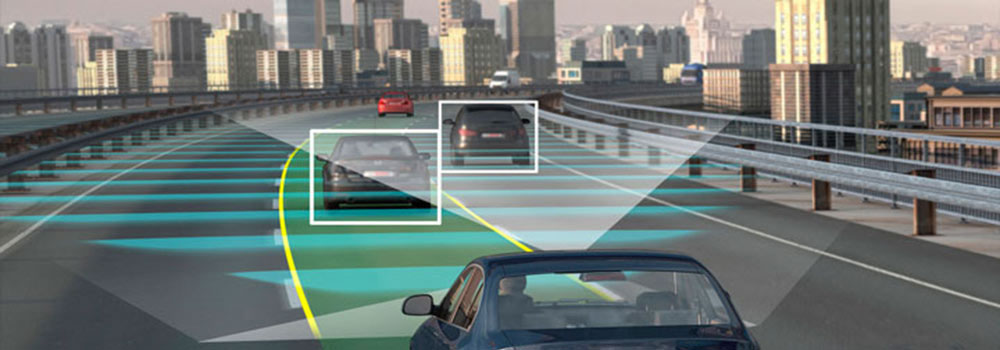

Robot localization is one of the most fundamental problems in mobile robotics. There are multiple instances of the localization problem with different difficulties (cf. [NEGENBORN, pp. 9 – 11]). In this article, we shall deal with the problem that the robot is given a map of the environment and then either needs to keep track of its position when the initial position is known, or localize itself from scratch when it could theoretically be anywhere.

One might use methods like GPS for positioning, but in many scenarios it is not accurate enough. Self-driving cars, for example, need a few centimeters accuracy to be considerable for road traffic. As everyone with a car navigator knows, the accuracy for GPS can be grim. Therefore, it is not always an option. Since there is no reliable sensor to measure a position directly, we need to rely on other observations and infer the actual position from it. A possible way to do so would be to install cameras, use pattern recognition to spot landmarks whose positions on the map are known, determine the distances of the landmarks and then use trilateration to determine the robot’s position.

It is reasonable to assume that the distance sensors are noisy. It becomes even more difficult when we assume that the robot is moving through the world, because movement is usually noisy as well: Even though the robot can control its average speed, motors are subjected to an unmodeled inaccuracy, resulting in unpredictable speed variations. As we can see, this is a situation as described in the previous section: The robot cannot infer its exact position from sensor data and, even if it does know its exact position at a certain point in time, it does not know it for certain anymore a moment later. This is due to the fact that the model it uses to describe the environment cannot describe the marginal factors that cause the motor to be inaccurate. As such, this problem is a good example for filtering and will therefore be used to elucidate the algorithms presented in this article.

Recursive Bayesian Estimation

Before we can deal with the concrete filter algorithms, we have to lay a theoretical foundation. In this article, we will model the world in such a way that all the changes in the environment take place at discrete, equidistant time steps $t \in \mathbb{N}_0$, where sensor measurements arrive at every time step $t \geq 1$. To model uncertainty over continuous time is more difficult, since it involves stochastic differential equations. The discrete-time model can be seen as an approximation at the continuous case. [NORVIG, p. 567]

State

At each point in time $t$, we can characterize a dynamic system by a state vector $x_t$, which we simply call the state. This state vector contains the so-called state variables that are necessary to describe the system. We assume that it contains the same state variables at each time step. We define the so-called state space $dom(x_t)$ as the set of all the possible values that $x_t$ might take. If we consider a moving robot on a plain, the state could be $x_t = (X_t, Y_t, \dot{X}_t, \dot{Y}_t)$ where $X_t$ and $Y_t$ refer to the robot’s current position and $\dot{X}_t$ and $\dot{Y}_t$ to its movement speed in the X and Y direction, respectively. In this case, the state space would be $dom(x_t) = \mathbb{R}^4$.

For each environment, there are virtually infinitely many possible state vectors, where additional state variables generally make the description of the environment more precise, with the downside of increasing the computational complexity of maintaining a belief. For example, if we consider the robot on a plain again, we could include the wind direction and force in the state vector to account for variations in the robot’s movement that are caused by the wind.

A state is called complete if it includes all the information that is necessary to predict the future of the system. In realistic examples, the state is usually incomplete. For example, if we assume that there are human beings interfering with the robot on the plain, then the state would have to include data that makes it possible to predict their decisions, which is practically impossible. Even in situations where we could in principle include all the influencing factors in the state, it is still often preferable not to include them to reduce computational complexity. In practice, the algorithms described in this article have turned out to be robust to incomplete states. A rule of thumb is to include enough state variables to make unmodeled effects approximately random. [THRUN, p. 33]

As alluded to in the introduction, the state $x_t$ is usually unobservable, which means that we cannot measure it directly. Instead, we have sensors that generate a measurement $e_t$ at each time step $t \geq 1$, which is a vector of arbitrary dimension. This measurement vector contains noisy sensor measurements that are caused by the state. In our modeling, $e_t$ always contains the same measurement variables. If we have a GPS sensor, then this measurement vector could consist of the measured X and Y coordinates. It is important to realize that these measured coordinates are generally not the same as the actual coordinates. Instead, they are caused by the actual coordinates but underlie a certain measurement noise due to the inaccuracy of GPS.

Belief

As we said, the state $x_t$ is unobservable. All we can do is maintain a belief $bel(x_t)$, given the observations. The process of determining the belief from observations is called filtering or state estimation (cf. [NORVIG, p. 570]). In mathematical terms, the belief is a probability distribution over all possible states, conditioned by the observations so far: $bel(x_t) := P(x_t \mid e_{1:t})$, where we use $e_{1:t}$ as a short-hand notation for $(e_1, e_2, …, e_t)$.

We also define $\overline{bel}(x_t) := P(x_t \mid e_{1:t−1})$, which is the projected or predicted belief, i.e. the probability distribution over all the possible states at time $t$, given only past observations.

As we can see, the number of measurements we have to condition by in order to determine the belief increases unboundedly over time. This means that we would have to store all the measurements, which is impossible with a limited memory. Additionally, the time needed to compute the belief would increase unboundedly, since we have to consider all the measurements so far. If we want to have a computationally tractable method for calculating the belief at deliberate points in time, we have to find a function $f$ such that $bel(x_{t+1}) = f(bel(x_t), e_{t+1})$. This means that in order to calculate the belief at a certain time step, we take the belief of the previous time step, project it to the new time step and then update it in accordance with new evidence. Such a method is called recursive estimation (cf. [NORVIG, p. 571]). The Bayes Filter is an algorithm for doing this. But before we can formulate the algorithm and prove its correctness, we have to specify how the world evolves over time and how we interpret sensor input. Also, as we will see in the next sections, we have to make some assumptions about the system in order to arrive at a recursive formulation.

Transition and Sensor Models

As stated in the introduction, realistic environments are non-deterministic but stochastic – given a state $x_t$, we can not tell what the state $x_{t+1}$ will be. Regardless of that, we can tell how likely each of the possible states $x_{t+1}$ is, given the state $x_t$. In mathematical terms, we can specify the conditional probability distribution $P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t)$. We call this distribution the transition model, since it is a model of how the environment transitions from one time step to the next.

Analogously, due to the partial observability of the environment (in particular, the inaccuracy of the sensors), we cannot tell which state causes exactly which sensor measurement, since there is always some measurement noise. However, we can tell how likely each possible sensor measurement $e_t$ is, given the state $x_t$. In mathematical terms, we can specify $P(e_t \mid x_t)$, which we call the sensor model. Given a sensor measurement $e_t$, it tells us how likely each state is to cause this measurement.

We will see examples for transition and sensor models in the following sections.

The Markov Assumption

In order to be able to arrive at a recursive formula for maintaining the belief $bel(x_t)$, we have to make so-called Markov assumptions about both the transition model and the sensor model. We will see in the next section that these two assumptions allow us to arrive at a method to calculate the belief recursively.

For the transition model, the Markov assumption states, that, given the state $x_t$, all states $x_{t+j}$ with $j \geq 1$ are conditionally independent of $x_{0:t−1}$ (cf. [DEGROOT, p. 188, 189]). This gives us $P(x_{t+1} \mid x_{0:t}) = P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t)$. Intuitively speaking, this assumption means that if we know the state at a certain point in time, then no previous states give us additional knowledge about the future.

We also make a sensor Markov assumption as follows: $P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1}, e_{1:t}) = P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1})$. This means that if we know the state $x_{t+1}$, then no sensor measurements from the past tell us anything more about the probabilities of each possible sensor measurement $e_{t+1}$.

The Bayes Filter Algorithm

As we stated in section 3.2, we want a method to calculate $bel(x_{t+1})$ from $bel(x_t)$ and $e_{t+1}$. We can do this in two consecutive steps First, we calculate the projected belief $\overline{bel}(x_{t+1})$ from $bel(x_t)$. This step is usually called projection: We project the belief of the previous time step to the current time step. We can do this in the following way (a proof for this statement can be found in [NORVIG, p. 572]):

$$

\overline{bel}(x_{t+1}) = \int_{x_t} P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t) bel(x_t)

$$

The process of calculating $bel(x_{t+1})$ from $\overline{bel}(x_{t+1})$ is called update: We update the projected belief with the new evidence $e_{t+1}$. This can be done as follows:

$$

bel(x_{t+1}) = \eta P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1}) \overline{bel}(x_{t+1})

$$

In this formula, $P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1})$ can be obtained from the sensor model. $\eta$ has the function of a normalizing constant. This means that we do not need to calculate it directly from its definition. In the discrete case, it follows from the fact that the probabilities need to sum up to 1. In the continuous case, it follows from the fact that the probability density function needs to integrate to 1 (cf. [DEGROOT, p. 105]).

For the recursive formulation to work, we need a prior belief $bel(x_0)$. Most commonly, we have no knowledge beforehand, in which case we should assign equal probabilities to each possible state. If we know the state at the beginning and need to keep track of it, we should use a point mass distribution. If we only have partial knowledge, we could use some other distribution.

The Bayes filter algorithm for calculating $bel(x_{t+1})$ from $bel(x_t)$ and $e_t$ can now be formulated as follows (cf. [THRUN, p. 27]):

Continuous Bayes Filter

- $\overline{bel}(x_{t+1}) = \int_{x_t} P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t) bel(x_t)$

- $bel(x_{t+1}) = \eta P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1}) \overline{bel}(x_{t+1})$

Under the assumption that $bel(x_0)$ has been initialized correctly, the correctness of this algorithm follows by induction, since we already showed that $bel(x_{t+1})$ is correctly calculated from $bel(x_t)$.

In principle, we now have a method to calculate the belief at each time step. The question arises, however, how we should represent the belief distribution. For finite state spaces, we can simply replace the integral with a sum over all possible $x_t$ and represent the belief as a finite table. We call this modified version the Discrete Bayes Filter (cf. [THRUN, pp. 86, 87]). We will see a concrete example for the discrete Bayes Filter in the next section.

Discrete Bayes Filter

- $\overline{bel}(x_{t+1}) = \sum{x_t} P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t) bel(x_t)$

- $bel(x_{t+1}) = \eta P(e_{t+1} \mid x_{t+1}) bel(x_{t+1})$

It becomes more difficult if we consider continuous state spaces. In this case, the belief becomes a probability density function (from now on abbreviated p.d.f.) over all possible states. The general way to represent such a function is by a symbolic formula. The problem arises that an exact representation of a formula for the belief function could, in the general case, grow without bounds over time (cf. [NORVIG, p. 585]). Additionally, the integration step becomes more and more complex and some p.d.f.s are not guaranteed to be integrable offhand. We are going to see three different solutions to this problem, all of which introduce a different way of representing the belief distribution: The Histogram Filter, the Kalman Filter and the Particle Filter.

Continue with Part II: The Histogram Filter.

References

[NORVIG] Peter Norvig, Stuart Russel (2010) Artificial Intelligence – A Modern Approach. 3rd edition, Prentice Hall International

[THRUN] Sebastian Thrun, Wolfram Burgard, Dieter Fox (2005) Probabilistic Robotics

[NEGENBORN] Rudy Negenborn (2003) Robot Localization and Kalman Filters

[DEGROOT] Morris DeGroot, Mark Schervish (2012) Probability and Statistics. 4th edition, Addison-Wesley

[BESSIERE] Pierre Bessire, Christian Laugier, Roland Siegwart (2008) Probabilistic Reasoning and Decision Making in Sensory-Motor Systems

[Math Processing Error]bel(xt+1)